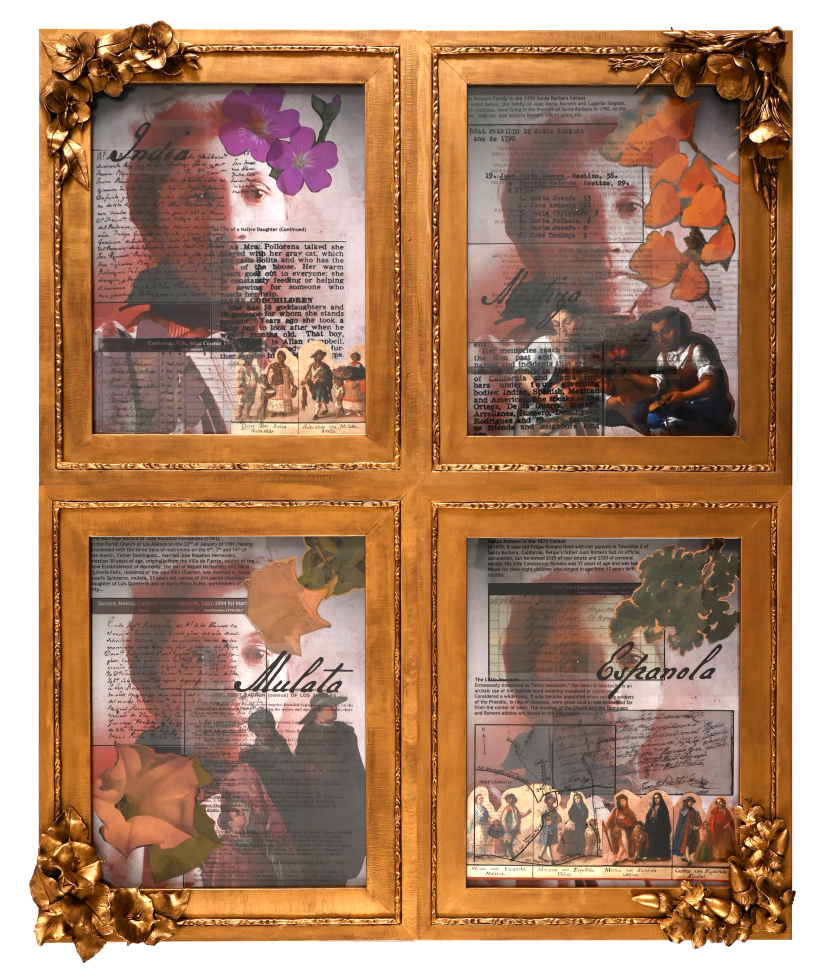

“It is time for the Mission Fantasy Fairy Tale to end. This story has done more damage to California Indians than any conquistador, any priest, any soldado de cuera, any smallpox, measles, or influenza virus . . .” — Deborah Miranda, Esselen/Chumash

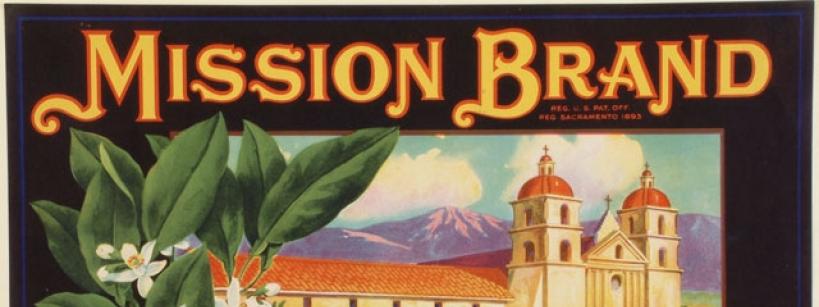

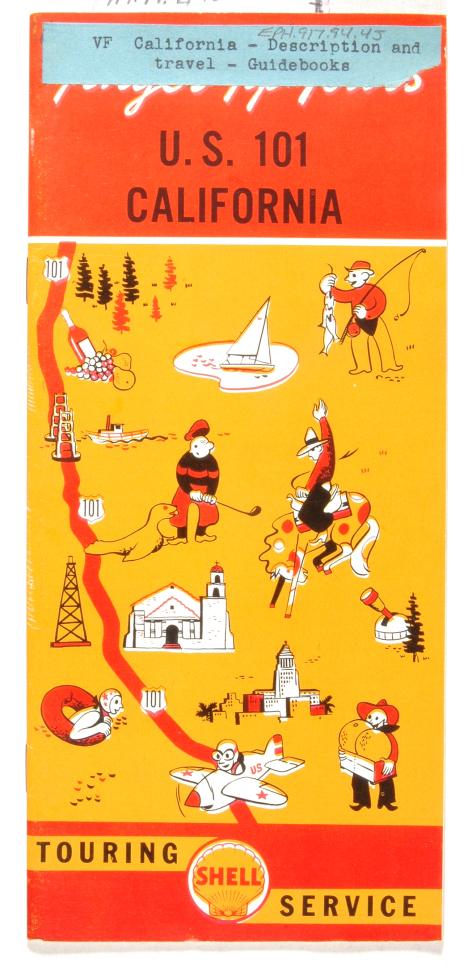

California was promoted in ads and newspapers as a Mediterranean paradise. Generated by men of industry, railroads, and land developers, this idea was an effort to entice white Americans to settle the West, which still had a reputation as a rugged frontier land. Their campaign to recast this narrative took shape as a revival of early California settlement, framing it as closely tied to its romantic Spanish heritage. Imagining a pre-modern lifestyle and Old World mecca inspired groups of “new Californians” to restore the dilapidated ruins of the missions. These efforts then gave birth to booster organizations like the Native Daughters of the Golden West, who worked to revitalize the missions and instill notions of “El Camino Real” as a romantic tourist destination and a vision of a tamed landscape awaiting settlement. In California, as elsewhere, the notion of open landscapes ripe for settlement required the further erasure of Native people and their visual presence.

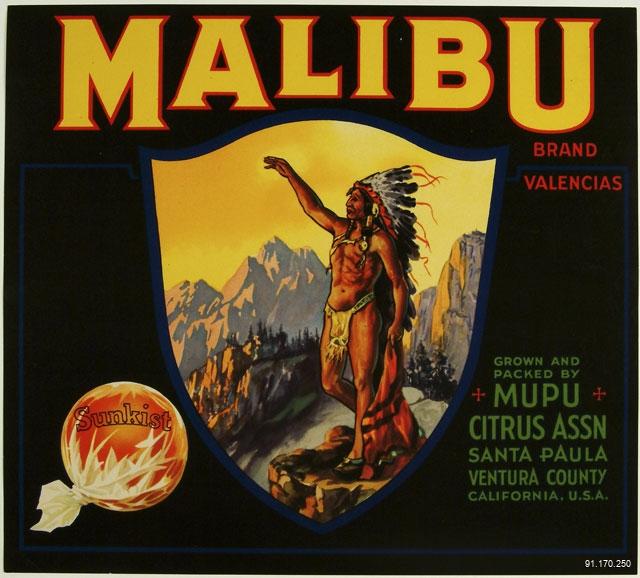

Various strategies have been used over the years to convince Americans that Native people are all “gone.” One strategy has been to depict Native people only in the past, and another is to dehumanize images of them, depicting them only as stereotypes. And yet another pervasive method has been to categorize them as immigrants and exploit them for labor. These strategies were perfected simultaneous to the flood of newcomers to California in the early 1900s, but most elements of Native and “Mexican” stereotyping can still be witnessed today. Native people on both sides of the U.S. border have continued to be used as laborers (usually today from south of the border) with few rights or access to the privileges of their white American neighbors. Almost completely forgotten is the reality that these are all Native lands and that the first peoples span the entirety of the Americas: a land that predates a border, and identities of Indian, Native American, Mexican, Latino, Chicano.