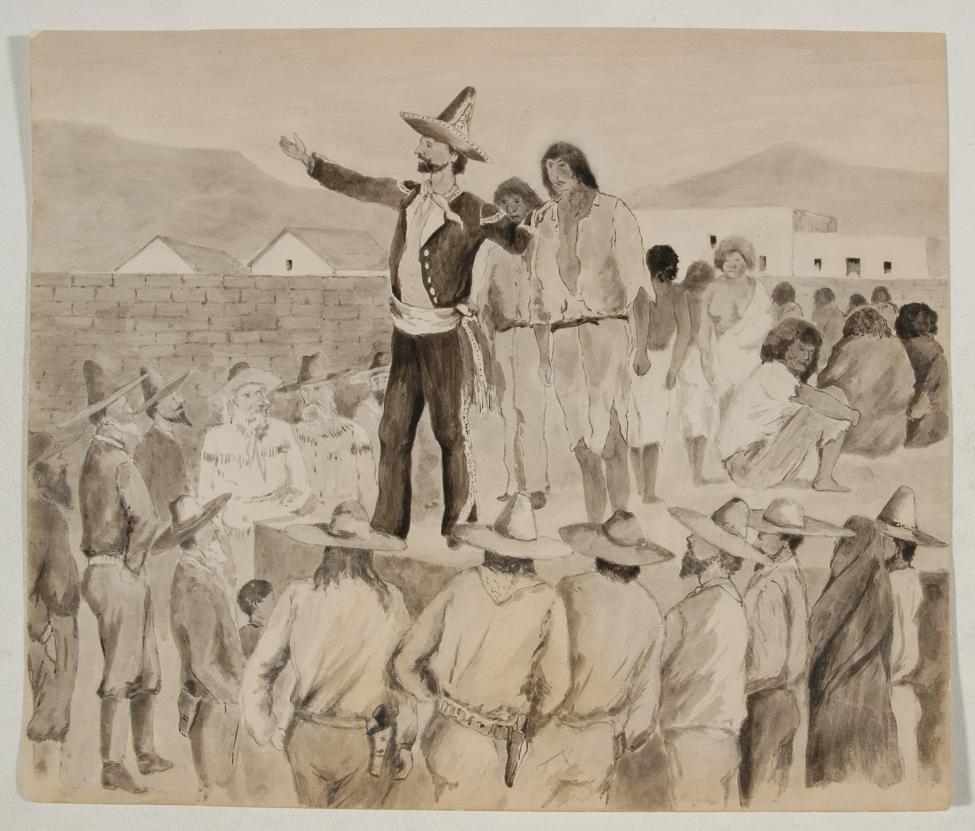

“Although forced recruitment and Indian peonage were part of life at the missions and ranchos, the actual buying and selling of California Indians was an American innovation . . .” — James Rawls, American historian

After the Mexican War of Independence, the Californias and its people were transferred to a Mexican government. The missions were “secularized,” meaning they were no longer supported as sites of forced assimilation, instruction, and enslavement by the Spanish crown. While this might have been seen as possible liberation for Native people, they were once again subject to laws and decisions that they had little control over. Under the Mexican constitution were stipulations that included the fair treatment and protection of the former mission “Indian” population—though unconverted Indians were seen as a threat to the people who identified as Mexican.

After the defeat of its army and the fall of the capital in September 1847, Mexico entered peace negotiations with the United States. Under the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico ceded Upper California and New Mexico to the United States. In further negotiations, Mexico also ceded 55 percent of its territory, including the present-day states of Nevada, Utah, and most of Arizona and Colorado. The treaty specified that the new U.S.–Mexico border will " preclude all difficulty in tracing upon the ground the limit separating Upper from Lower California. “A straight line was drawn from the mouth of the Gila River to three nautical miles south of the southernmost point of the port of San Diego, disconnecting language groups like the Ipai and Tipai (today known as the Kumeyaay) from their relatives. With yet another transfer of power came new ideas about managing Native peoples. Militias were formed and funded by the new American government, and bounties were placed on Native lives to clear the way for expansion by white settlers. Indian agents, U.S. government representatives who implemented federal policies on reservations, were empowered to identify and define Native communities. Those who seemed to have their culture intact and appeared to be living communally on their Indigenous lands negotiated treaties and moved to specific areas for their control and “protection,” usually away from their traditional territories and white population centers. Others, who had lost most of their connections and cultural knowledge during missionization, were considered assimilated and defined as extinct.