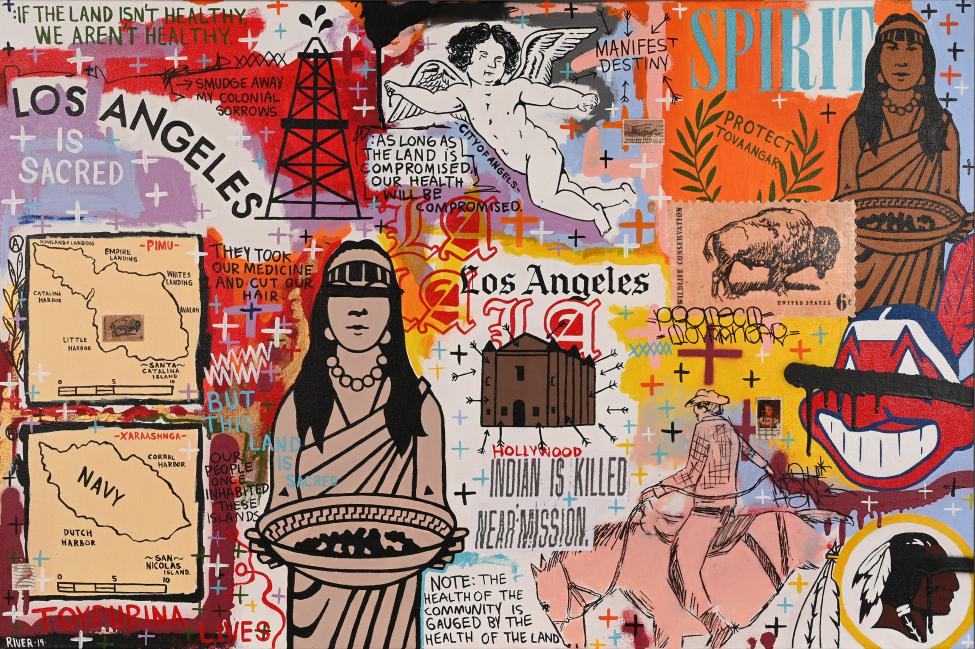

“RETURN TO THE SOURCE OF THE ORIGINAL WOUND. WALK WITH US. COMMIT TO STANDING IN ALLYSHIP WITH THE NATIVE PEOPLE OF THE CALIFORNIAS.” — L. Frank, Acjachemem and Rarámuri

Most Native groups along the El Camino, in former mission areas, are landless and continue to fight for tribal status or recognition as sovereign nations. Without land and resources, it is difficult to maintain ties to their land, culture, and community. Native people have fought to maintain a presence in their homelands; however, the area’s warm climate and unmatched beauty make it some of the most desirable real estate in the United States. Without Native stewardship of the coast, the persistent treatment of the land as a resource to be extracted from results in a violent and devastating response from the environment.

Examples of Native Survivance is all around. Each year, fires and floods destroy human and nonhuman habitats in Southern California. Pressures including the high cost of living, alienation from the land due to the development of freeways and cities, border policies that further divide and define Native Americans, and the legacy of separation of the people from their traditional lives that depend on these connections.

Despite these pressures, many Native groups have continued to resist in a variety of forms. Today that resistance manifests as pressuring lawmakers toward policies for the preservation of sacred places, addressing unethical treatment of Native Ancestors, and protecting fragile ecosystems. These groups are also revitalizing traditional ecological knowledge by creating conservancies and partnering with private landowners to restore balance to the land—efforts that are healthy for everyone. Furthermore, many Native communities have invested in the revitalization of their languages, cultural traditions, and ceremonial life to assert their sovereignty and define an empowered future.

Despite previous attempts to erase them, Native peoples persevere because of their commitment and connections to their LAND, CULTURE, AND COMMUNITY.