On November 20, 1969, a group of Native Americans landed and occupied Alcatraz Island for 19 months. The initial group of over eighty occupiers referred to themselves as “Indians of All Tribes” reflecting the diversity of Native Americans in the Bay Area during this time period. The Bureau of Indian Affairs Relocation Program began in 1948 and encouraged Native peoples that resided on reservations and rural Native communities to leave their homelands and assimilate in large urban cities. As one of the targeted areas for relocation, the Bay Area received a large influx of Native Americans from across the country. This facilitated new communities to be formed that were Intertribal in nature. Through this Intertribal dialogue, Native Americans from different communities shared a common history: the oppression and lack of respect by the federal government for generations. Organized, activated, and well informed of their history, the Indians of All Tribes’ action was a call to all Native Americans across the country to stand up for their rights and communities. During the several months of the takeover, more than 10,000 from over 130 Tribes visited the island from all over the country.

The impact of the occupation of Alcatraz cannot be overstated. It is considered the first major national occupation for collective Indigenous rights and land liberation. This event influenced Indigenous takeovers across the country and around the world. Among many Native Americans today the power of Alcatraz takes on a certain aura, a time when our parents, grandparents set the tone for us to follow- to stand up for our People.

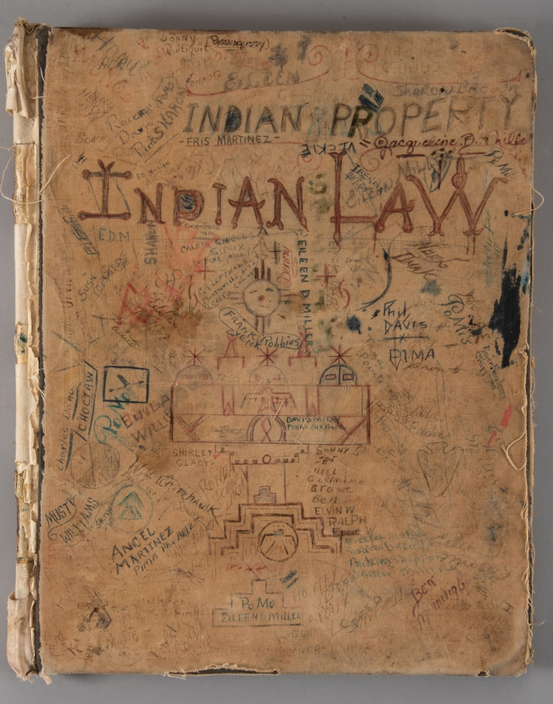

Much of the history of the occupation and its key players have been recorded elsewhere, but one key element of the story has been missing. A logbook of those who visited the island exists and is presented here to the public for the first time. Although only a fraction of those that visited the island signed the book, it does provide us greater insight into the diversity and numbers of people who visited and stayed on the island. A brief overview of the 254 pages shows names of Native Americans that are common household names like Wilma Mankiller and John Trudell.

On the first page of the book, Luwana Quitiquit (Pomo) writes, “HISTORY This book found in the old broiler room by myself brought to the pier for registration new residence and visitors on December 7, 1970.” Native scholar Kent Blansett, author of A Journey to Freedom: Richard Oakes, Alcatraz, and the Red Power Movement and the founder and executive director for the American Indian Digital History Project, after seeing the logbook states that “it's one of the most significant artifacts of the Red Power era.”

For every name that was signed into the book there is a story. A family story of activism, community, and determination. A story that we can share to honor those that set the standard for us and serve as an inspiration to continue to move forward.