Library and Archives

For more information about accessing the collections, see the Libraries and Archives pages.

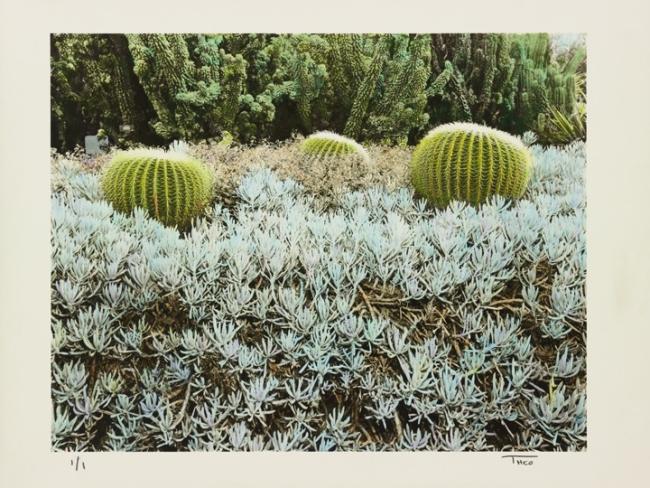

Three Barrel Cactus, Huntington Gardens, California, circa 1970. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.43.2A

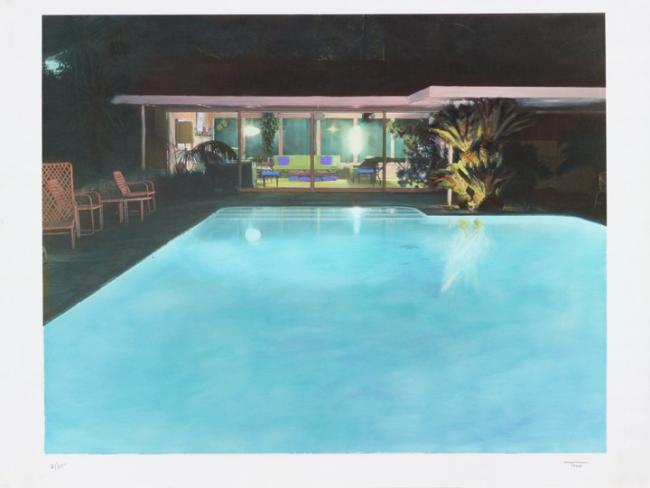

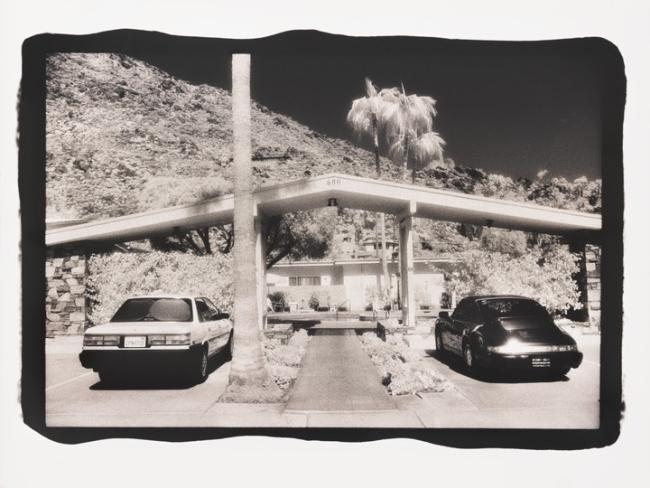

In 2010, the Library and Archives of the Autry received a generous gift: the entire photographic work of Theo Westenberger (1950–2008). The Autry embraced Westenberger as a true woman of the West. She had a Western childhood and, in her early photography, captured the essence of both the natural and constructed California landscape. Westenberger’s success as a commercial photographer in New York brought her back to California as a player in the movie industry, where she worked with new and established stars. It was in her personal fine art work, however, that her California roots were revealed. She photographed the Rose Parade from 1974 to 1980 and was clearly fascinated with Western culture and the elaborate costumes worn by horses and riders alike. Throughout her life she photographed contrasts. She photographed the “kitsch” architecture of Los Angeles and the sleek midcentury architecture of Palm Springs, and the dense luscious gardens of San Marino as well as the sharp, bristled Joshua trees of the Mojave Desert. Even when we look at images Westenberger shot in the gardens of Italy or the jungles of Guatemala, we see elements that are familiar to us from her work in California.

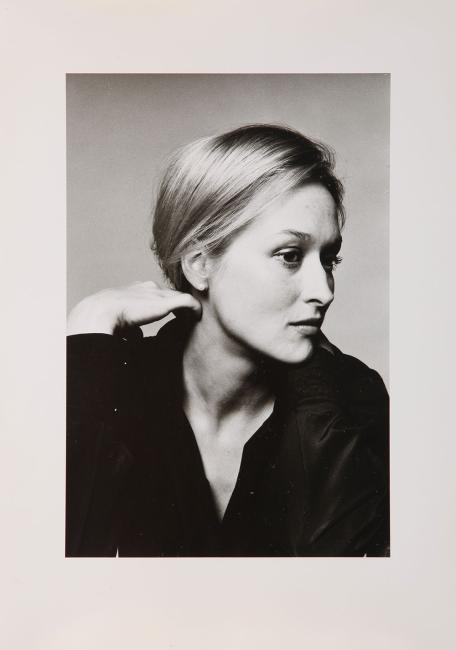

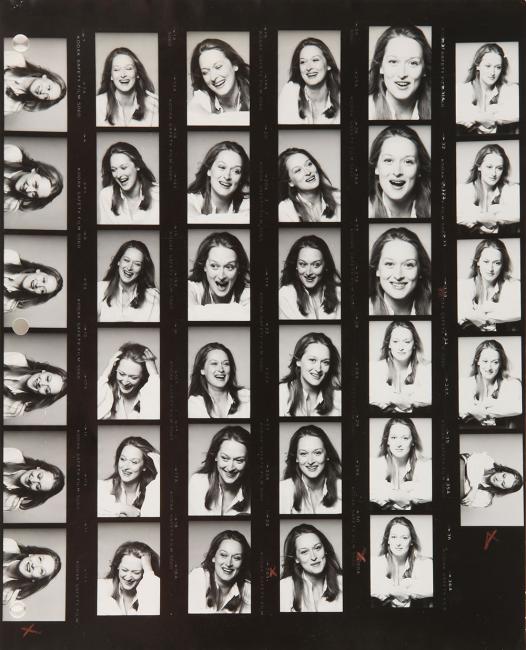

Meryl Streep, portrait, New York, 1977. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.226.2A

Neutra House, Altadena, California, circa 1970. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.42.2A

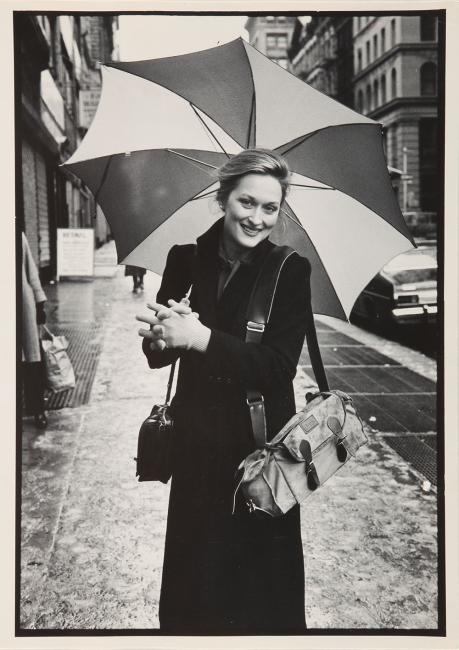

Meryl Streep, New York City, 1978. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.225.2A

Three Barrel Cactus, Huntington Gardens, California, circa 1970. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.43.2A

The Red Golf Ball, miniature golf course, San Fernando Valley, California, circa 1970. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.205.2A

Carport, Palm Springs, California, 1990. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.11.3A

Theo Westenberger was born in Los Angeles in 1950, raised in Pasadena, California, and finished high school at the Norton School, Massachusetts. After graduating from Wheaton College in 1972, she worked as a gallery owner in Boston and later as a studio manager and photographer’s assistant in New York. Westenberger was initially interested in architecture and landscape photography, working extensively with 4x5 and 5x7 cameras, and shooting buildings and gardens in Southern California, Mexico, and Ireland.

While she was studying for an MFA at Pratt institute from 1976 to 1978, Westenberger found that photographing people was her forte. Her ebullient spirit and willingness to laugh put her subjects at ease. Fortuitously, when Westenberger was an exchange student at Dartmouth College in 1971, her roommate was an aspiring actress named Meryl Streep. After their graduate work, they met again in New York in 1978 when Ms. Streep was already making her mark on the New York stage. As a friend, Westenberger was able to catch her natural beauty and spontaneity. Those photo shoots were widely published and helped bring the talents of both women to the attention of Hollywood and the national press.

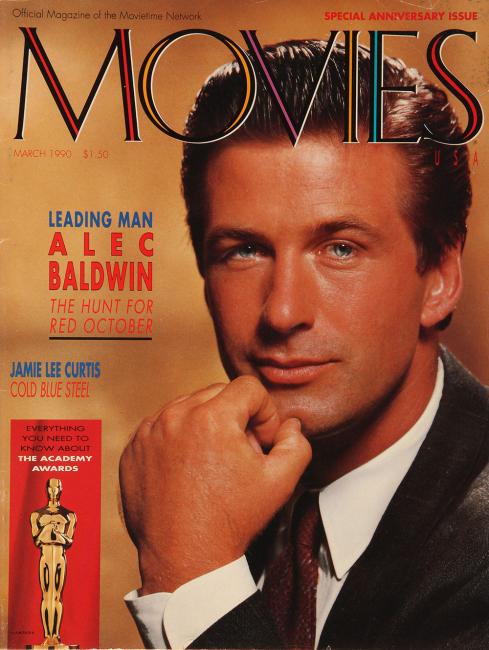

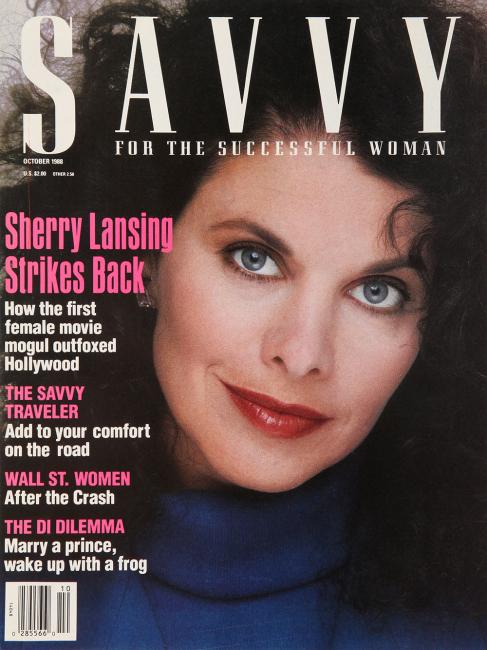

In 1979 Westenberger was hired as a junior photographer for Look magazine when it was revived by Hachette Filipacchi. She worked as a photojournalist covering events, parties, and celebrities. Although Look folded some six months later, Westenberger had made by then her mark, and for the next decade she was a sought-after freelance photographer for all the leading national magazines. A self-confident woman who was never “star-struck,” she excelled at photographing and interacting with high-profile musicians, actors, celebrities, and sports stars. At the same time, she welcomed assignments with “real people”—to use her own term!

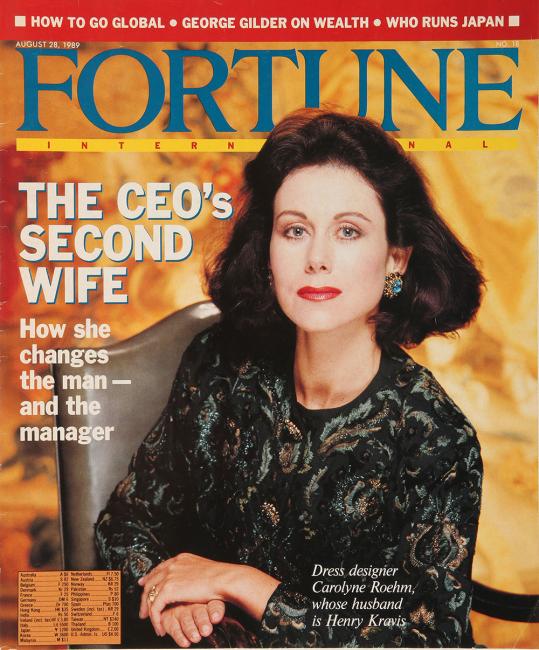

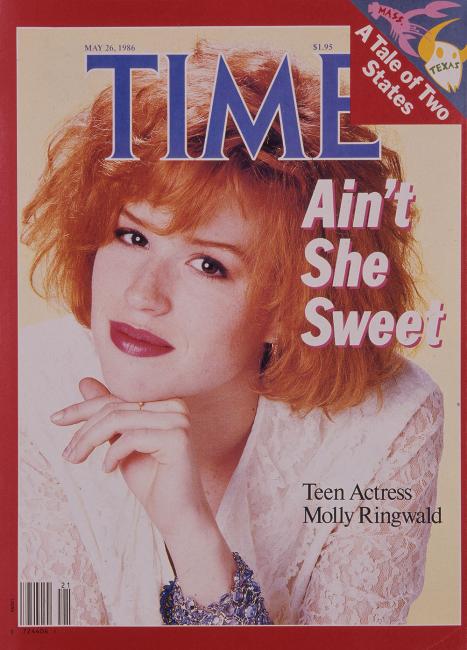

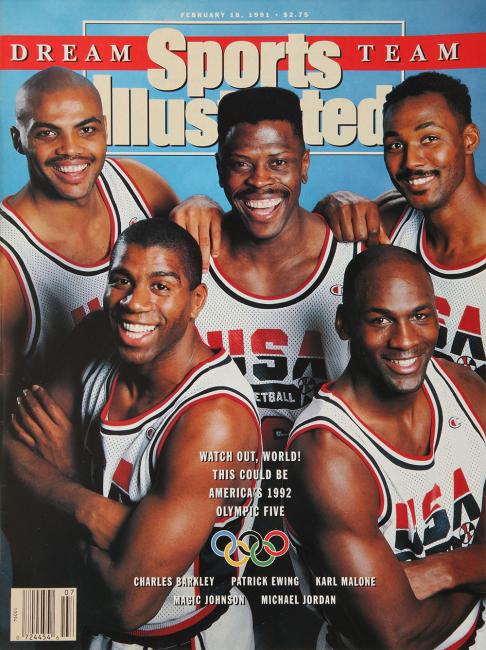

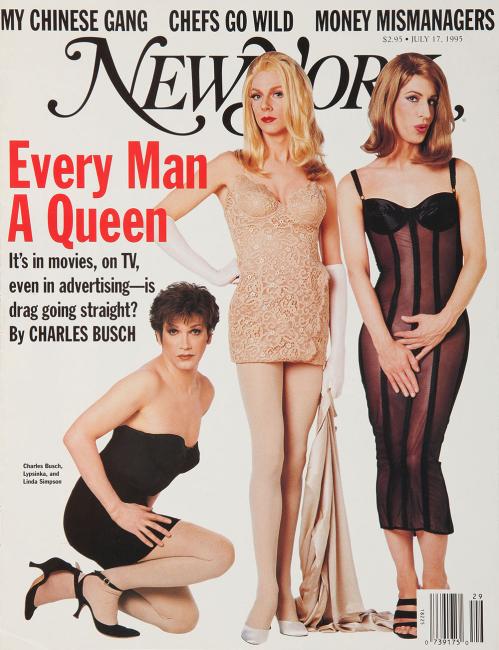

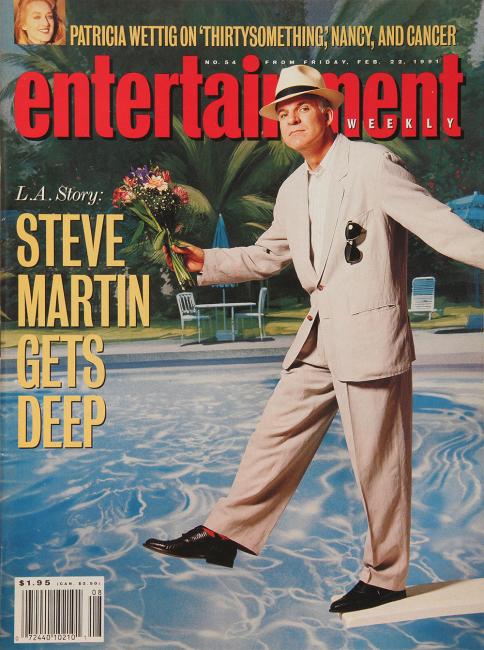

Among her many clients were Savvy, Money, Rolling Stone, Life, Paris Match, Sports Illustrated, New York, Bunte, Stern, Time, Forbes, Fortune, Premiere, and Family Circle.

Westenberger worked extensively on movie sets for magazines and the publicity departments of the leading movie studios. She was hired to produce “special photography” for their marketing, advertising, and magazine covers. She shot A-list movie stars for Entertainment Weekly, Life, and TV Guide. This cover of Steve Martin epitomizes the sense of humor that helped her capture the personality of her subject and shows off her skill in creating an illusion for the camera.

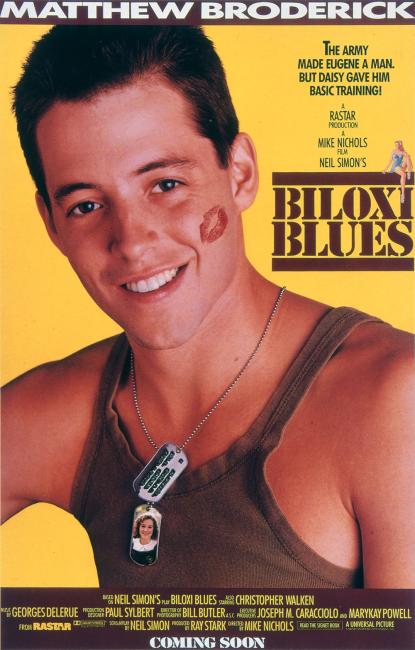

Between 1981 and 2005, Westenberger worked as a photographer on 51 movies for studios such as Universal, Warner Brothers, Paramount, New Line Cinema, 20th Century-Fox, and Carolco Pictures, resulting in fifteen movie posters to her credit. Her last shoot for a movie studio client was in December 2005 with her friend Meryl Streep on the set of the movie The Devil Wears Prada.

Alec Baldwin, Movies Special Issue, March 1990. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.229

Carolyne Roehm, Fortune, August 28, 1989. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.230

Sherry Lansing, Savvy, October 1988. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.232

Molly Ringwald, Time, May 26, 1986. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.240

Charles Barkley, Patrick Ewing, Karl Malone, Magic Johnson, Michael Jordan, Sports Illustrated, February 18, 1991. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.248.2A

Drag queens, New York Magazine, July 17, 1995. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.234

Steve Martin, Entertainment Weekly, February 21, 1991.Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.228

Biloxi Blues, movie poster featuring Mathew Broderick, 1988. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.242

Planes Trains and Automobiles, movie poster featuring Steve Martin and John Candy, 1987. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.241.2

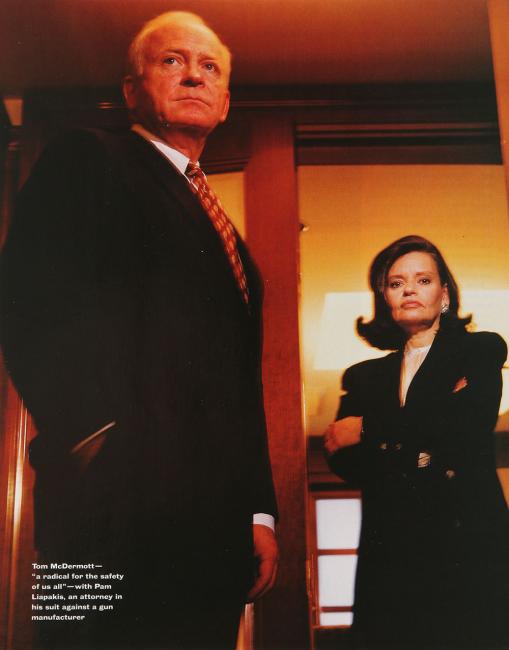

Attorney and client, Worth, April 1995. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.235

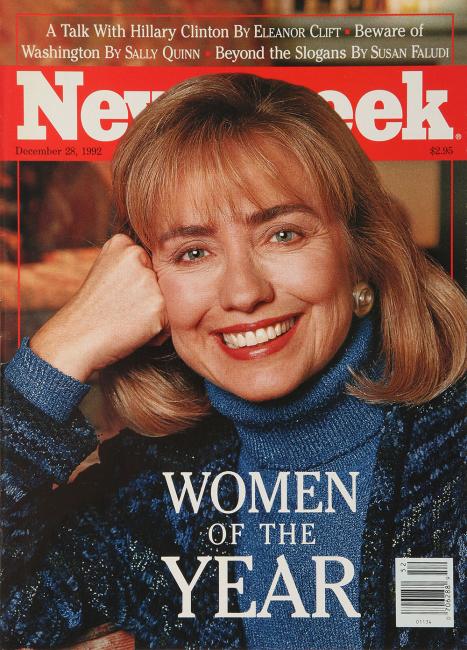

Hillary Clinton, Newsweek, December 28, 1992. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.227

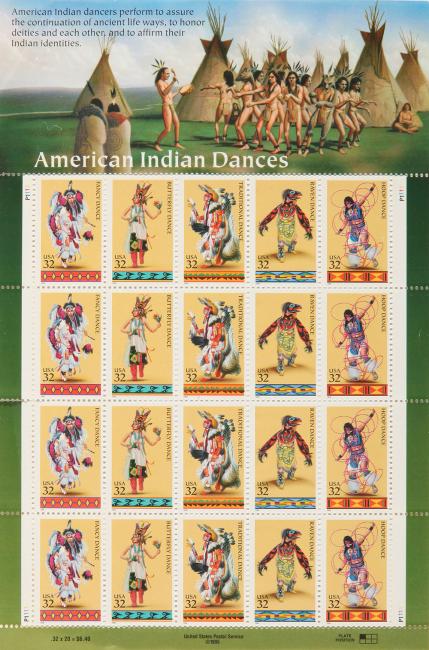

American Indian Dance Theater, sheet of 32-cent U.S. postage stamps, 1996. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.239

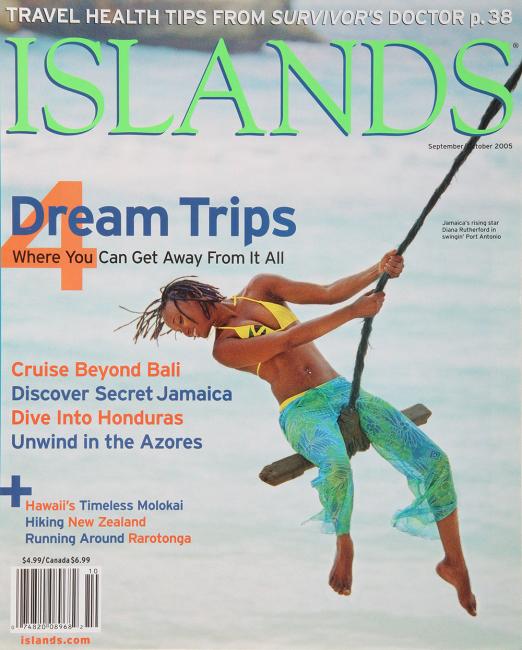

Jamaica, Islands, September–October 2005. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.236

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Westenberger established herself as a leading portrait photographer who could handle any type of personality and, because of her meticulous planning, could work under the unavoidable pressures of time. Westenberger was always in demand to shoot CEOs and other influential businessmen and -women, who rarely gave her more than twenty minutes to shoot. Her dramatic lighting and composition lent interest and gravitas to these executives.

Westenberger also photographed four U.S. presidents, two vice presidents, and their wives for Time, as well as the leading women politicians in the country, including Hillary Clinton, who was Newsweek’s Woman of the Year in 1992.

An active member of the photography community, Westenberger won numerous awards, and her work was exhibited in fifteen shows during her lifetime. She taught photography workshops in Woodstock and Maine, and at the prestigious Santa Fe Workshops. Westenberger was honored in 1996 when the U.S. Postal Service created 32-cent stamps using two of her images of the American Indian Dance Theatre, originally shot for Smithsonian Magazine in 1992.

During the 1990s, Westenberger started getting assignments as a travel photographer. She excelled at this kind of photography because her curiosity and zest for life were infectious, and she made friends who opened doors for her wherever she went. Her travel pictures were intimate and alive, full of people, color, and food. She contributed to Smithsonian, National Geographic Traveler, Conde Nast Traveler, andTravel Holiday. From 1989 to 2000 she completed assignments in, Miami, Australia, Brazil, France, Spain, and Portugal. In the 2000s she made trips to China, Thailand, and Hong Kong in addition to her work for Islands magazine, which took her to Puerto Rico, Martinique, St. Vincent, Jamaica, and Grenada. Westenberger was often asked to write short pieces about her experiences on assignment for these same magazines.

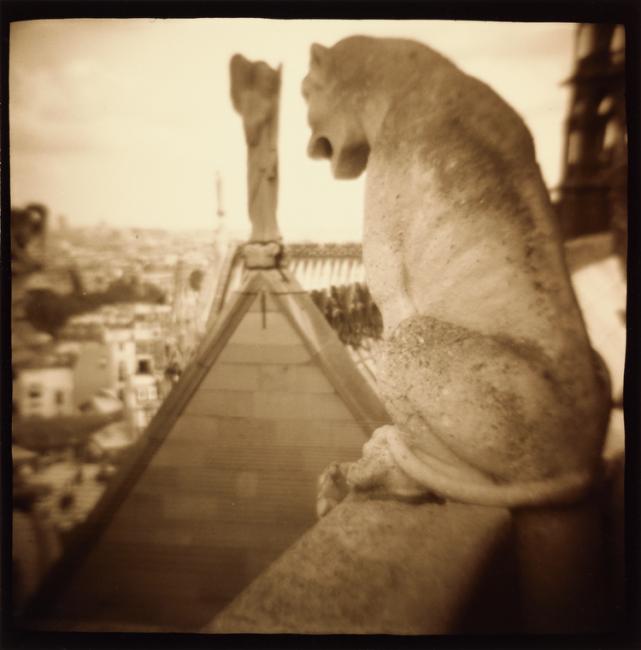

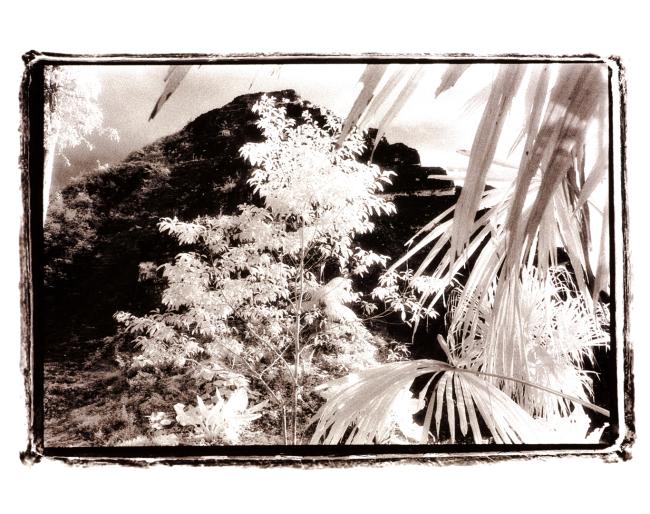

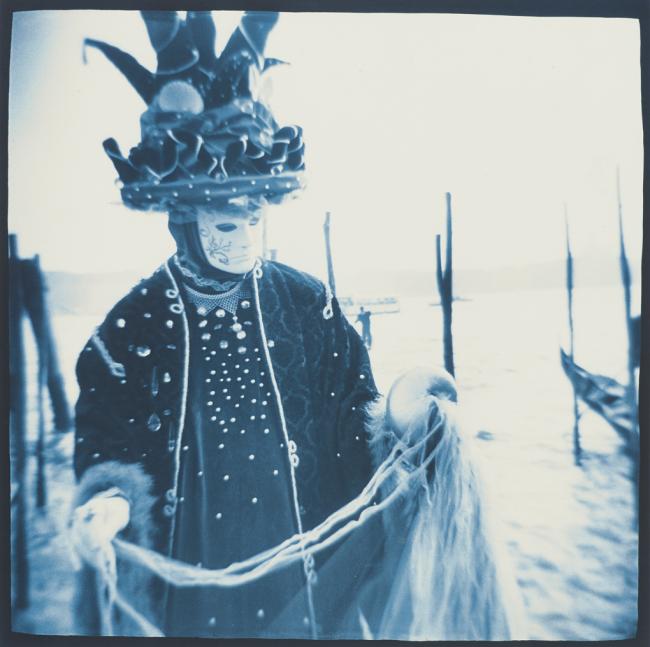

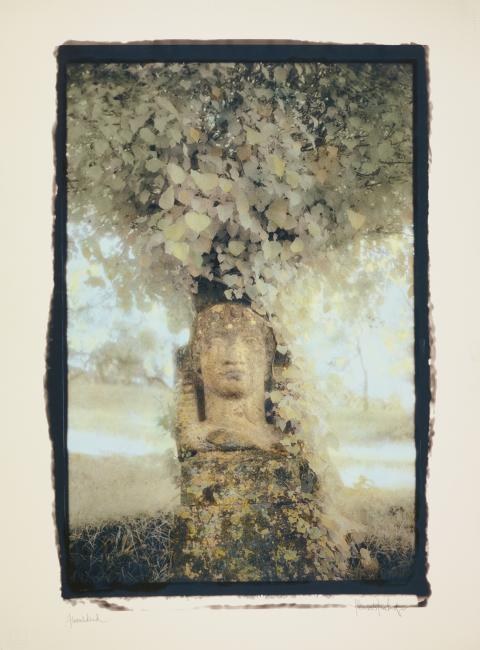

Westenberger’s success provided her with the resources to travel and focus on her fine art work. In 1989 she traveled and photographed in Thailand. In the 1990s she made multiple trips to Italy, France, India, and Guatemala. On these trips she produced fine art work that contrasts stylistically and technically with her commercial assignment work. Westenberger’s preferred cameras while traveling were often cheap plastic cameras with the brand names Diana or Holga, both of which were mass produced as toys. The results were unpredictable, less-than-sharp, and vignetted images. These imperfections add a mysterious, soulful quality and timelessness to her images.

Westenberger also used infrared film in her Nikon FE camera. She was very aware of the resulting tonal changes and contrast shifts, using this film to produce dramatic, ethereal images that, when printed, became the perfect canvas for the oil paint she applied to create one-of-a-kind, hand-colored prints.

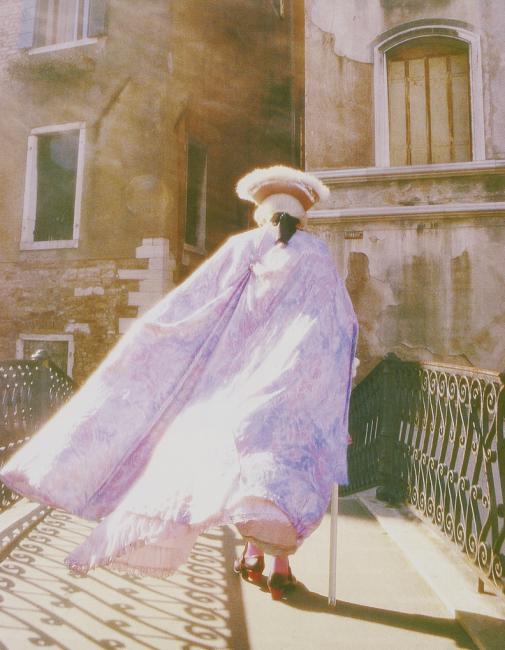

Westenberger had a lifelong interest in costumes, parade, and pageantry—influenced, no doubt, by the Rose Parade in Pasadena. Her visit to Venice for Carnevale in 1996 produced striking images of costumed characters at private balls, in cafés, and in the streets. Life magazine published some of these images in 1997, and she secured an assignment to shoot a cover story for National Geographic Traveler in 1998.

She researched other pre-Lenten rituals, and in 2002 went to Pjut in Slovenia to photograph the Kurentovanje Festival. The following year she shot the Carnival in Trinidad.

The Westenberger Archives show how this photographer’s fine art work began and matured during her lifetime. Through its contents, we can see Westenberger maintaining a very successful commercial career producing technically perfect, colorful images. In contrast, her fine art work embraced imperfection and unusual, unsophisticated tools that were combined with excellent printing and hand-coloring.

Mythical creature, Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris, 1994. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.119.2A

Waterways and Palaces, Venice, Italy, 1996. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.166.2A

Black Pyramid, Guatemala, 1990. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.102.2A

Vase, San Pietro di Positano, Italy, 1993. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.60.2A

Lost in Time, Venice, Italy, 1996. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.165.2A

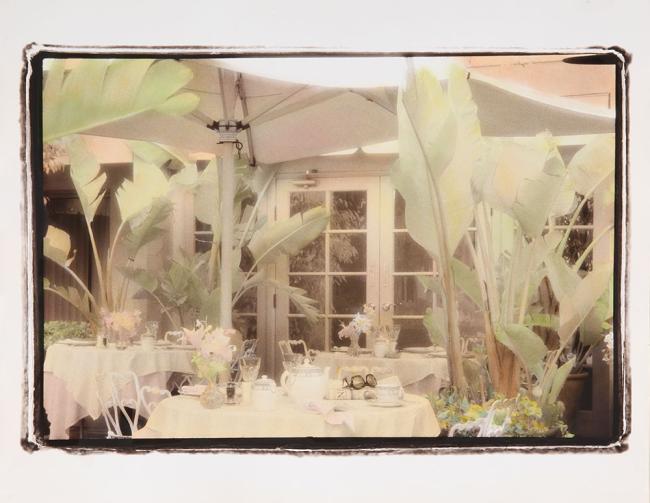

Patio With Palms, Sunset Marquis Hotel, Los Angeles, circa 1994. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.244.2A

The Count, Venice, Italy, 1996. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.178.2A

Boston Terriers Dieting, 2000. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.17.2A

Elephant’s trunk, Udaipur, India, 1996. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.21.2.1

On the Dock, Venice, Italy, 1996. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.151.3.1

By the 1990s, she was so well thought of and so well connected that she was hired to execute assignments in her personal style. She produced images for the Sunset Marquis Hotel in Los Angeles for use in advertising and for sale as fine art prints.

Although she did not succeed in securing a publisher, she continued to develop projects. We have book “dummies,” or layouts, and proposals for three other books. One, Great American Families, was inspired by a 1986 shoot for Life magazine called the “First Families of Film,” featuring such families as the Carradines, Douglasses, and Pecks.

In 2004 she produced a book dummy called Venice Unmasqued, featuring her images of the Venice Carnevale photographed between 1996 and 1998.

Westenberger, who had been adopted as an infant, found her birth mother in 2001. Inspired by this joyful experience, she proposed a book about adoption called Twice Born and applied for a Guggenheim Fellowship to complete the project.

Westenberger married Jay Colton in 1987, and they divorced in 1991. In 2004 she was diagnosed with lung cancer. Because she had so many friends in the photography business and did not want to stop working, she kept her illness private. In November 2007 she photographed Calvin Trillin for Architectural Digest. This turned out to be her last assignment. She passed away on February 28, 2008.

The Theo Westenberger Archives are complete records of all the photographs this artist took throughout her life, from her earliest amateur images in 1971 through her MFA show and her entire professional career, ending with her last born-digital assignments in 2007. There are 400 linear feet of materials, including negatives, transparencies, contact sheets, and prints. Westenberger used an extensive range of black-and-white and color film types, printing papers, toners, and cameras. Study of these materials offers insight into the tools and techniques available to a professional photographer in the late twentieth century prior to the industry’s adoption of digital cameras and printers.

Westenberger learned and practiced film developing and printing at Pratt Institute, but in her professional life she did not develop or print her own work. She engaged photo labs to make her commercial and portfolio prints and worked closely with experienced printers to produce her fine art prints. She kept her test prints and many—with printers’ annotations—are now part of the archives. The variety of prints, using different papers and chemical toners, reveals the laborious and expensive nature of producing the perfect silver gelatin print. In addition, many photographs are printed with irregular borders created by hand-crafted negative holders.

Westenberger was an early adopter of new printing technology. She was fascinated by the new digital “Iris” printer developed by Nash Editions in Los Angeles to produce fine art prints on heavy watercolor paper. In 1994 Nash Editions scanned and printed some of her hand-colored photographs of Italian gardens. The Autry has about fourteen of these rare original digital prints.

Meryl Streep, contact sheet, New York, 1977. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.9.1

Floral Head, Italy, 1993. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.63.2A

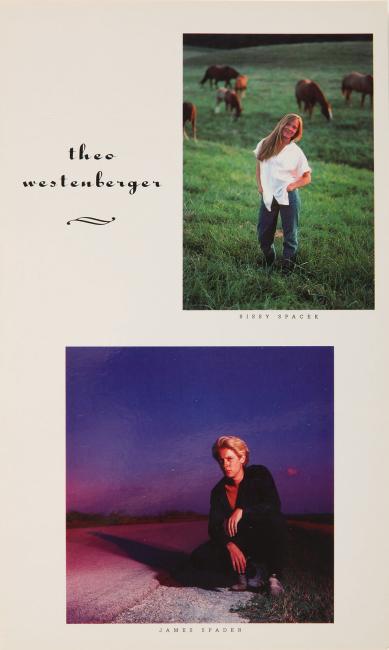

Theo Westenberger, printed card, self-promotion, with Sissy Spacek and James Spader, circa 1985. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.247.2A

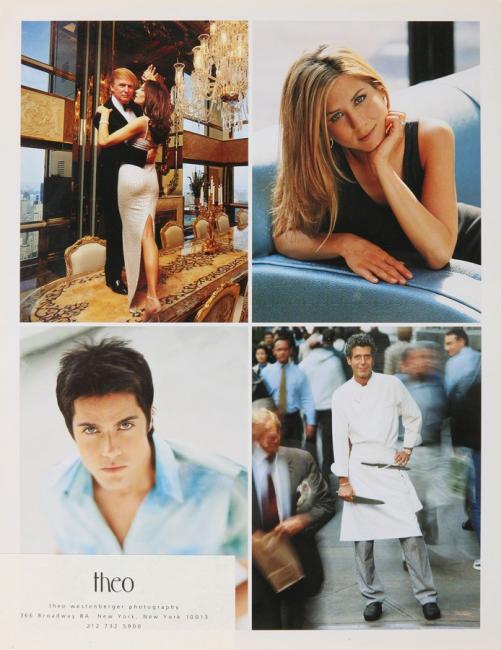

Theo Westenberger, printed card, self-promotion, featuring (clockwise from top right) Jennifer Aniston, Anthony Bourdain, Innis, and Donald and Melia Trump, circa 2003. Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974–2008. Autry Museum; MSA.25.245.2A

The Theo Westenberger Archives are records of the work of a professional editorial photographer from 1980 to 2000. She shot for such influential magazines asTime, Life, and Newsweek, which were important national outlets for news and opinion. A large amount of material remains for most of the assignments and in them we can see the scope of each job, the test shots, the lighting choices, the edits, the magazine’s selections, and secondary edits by Westenberger that isolated her favorite images. We can tell who were considered the most popular stars of the time from the images chosen, duplicated, and syndicated by her photo agents, Gamma Liaison and Sygma.

The Westenberger Archives also provide insight into the competitive nature of editorial and advertising photography in this era. Westenberger excelled at self-promotion.

She shot clever and humorous self-portraits to send as Christmas cards and printed her own black-and-white and color cards, known as “promos” or “mailers,” to send to prospective clients. Photographers maintain portfolios to show their work to advertising agencies and magazines. The Autry is lucky to have twenty-one of Westenberger’s portfolios, which represent and display the variety of marketing techniques and portfolio materials used by professional photographers from 1980 to 2004. Westenberger had custom-made photo albums lined in marbleized paper and portfolios made from red ostrich skin, lime green leather, and brushed aluminum.

We have taken steps to stabilize and preserve the materials in the Theo Westenberger Archives, which documents the career of a late twentieth-century female photographer with roots in California. The archives are now accessible to future photographers, researchers, publishers, and scholars, ensuring that Westenberger’s significant talents, commercial success, and intriguing fine art work will continue to inspire.

For more information about accessing the collections, contact the Libraries and Archives of the Autry at rroom@theautry.org.

For more information about accessing the collections, see the Libraries and Archives pages.

The Autry Museum of the American West acknowledges the Gabrielino/Tongva peoples as the traditional land caretakers of Tovaangar (the Los Angeles basin and So. Channel Islands). We recognize that the Autry Museum and its campuses are located on the traditional lands of Gabrielino/Tongva peoples and we pay our respects to the Honuukvetam (Ancestors), ‘Ahiihirom (Elders) and ‘Eyoohiinkem (our relatives/relations) past, present and emerging.

4700 Western Heritage Way

Los Angeles, CA 90027-1462

In Griffith Park across from the Los Angeles Zoo.

Map and Directions

Free parking for Autry visitors.

MUSEUM AND STORE HOURS

Tuesday–Friday 10:00 a.m.–4:00 p.m.

Saturday–Sunday 10:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m.

DINING

Food Trucks are available on select days, contact us for details at 323.495.4252.

The cafe is temporarily closed until further notice.