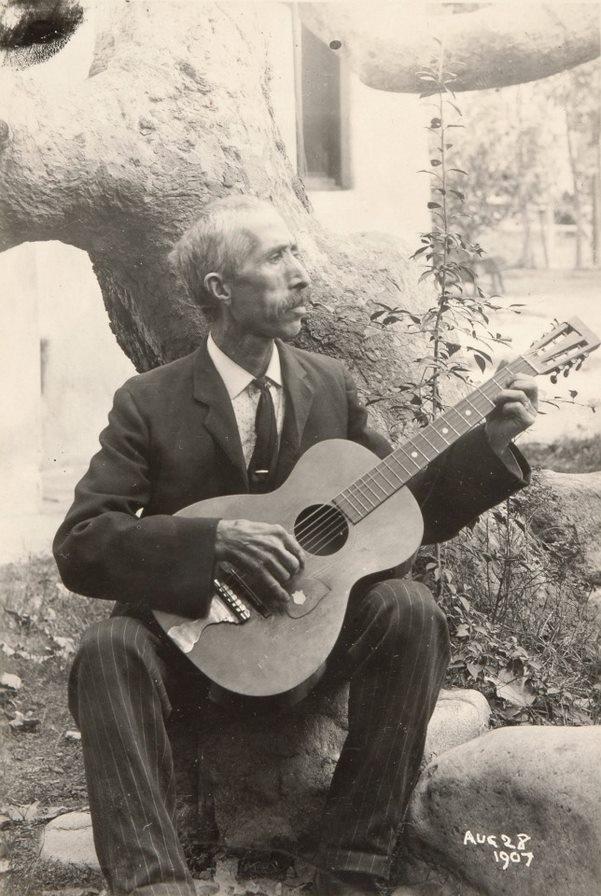

Charles Lummis, founder of Los Angeles's Southwest Museum, dedicated much of his life to preserving cultures that he felt were vanishing. Like a number of Americans at the turn of the twentieth century, Lummis was convinced that Native Americans’ lifeways were on the road to extinction, and that Hispanic cultures in particular were doomed by modernity. Unlike many of his contemporaries, however, Lummis lamented these developments and worked to preserve at least some records of Indian and Hispanic cultures.

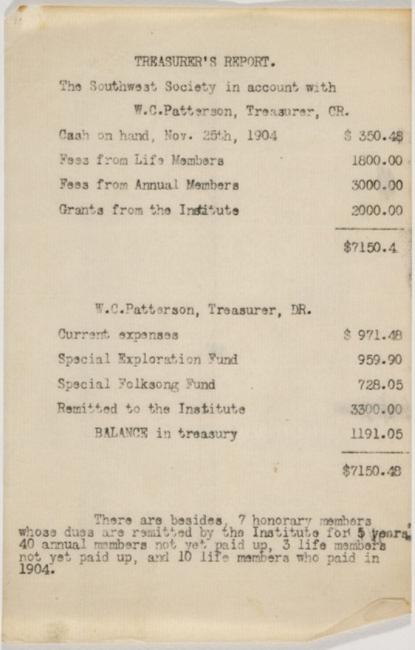

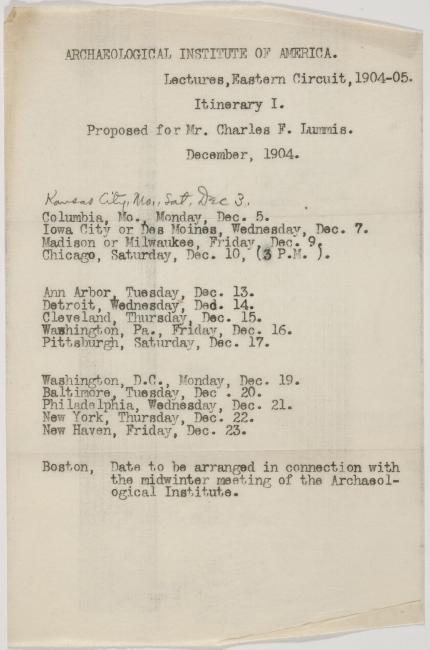

In 1903, he established the Southwest Society, the western branch of the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA). In 1907, he realized his ultimate goal of turning the organization into the Southwest Museum.

Key to the project of preservation was to save, by recording, the traditional music of Southwestern Indian and Hispanic cultures. In a 1905 article titled “Catching Archaeology Alive,” Lummis sought to persuade the AIA that his “large scale folk-songs of the Southwest project” was archaeology. Lummis argued that it wouldn’t be long before such artifacts were considered genuine archaeology. If not recorded now, he urged, the songs would be “as dead and gone as the rest.” The challenge was “to catch our archaeology alive.”

Lummis’s first introduction to the Southwestern folksongs dated to his tramp across America in 1884. He developed a greater understanding and interest in the Spanish folksongs later, as he recuperated from a stroke in the late 1880s, while living in New Mexico. He started to collect the lyrics of folksongs in his diaries and notebooks. His first published article about New Mexican folksongs appeared in Cosmopolitan magazine in 1890. He followed this with a more extended description of the songs in his 1893 book, Land of Poco Tiempo.

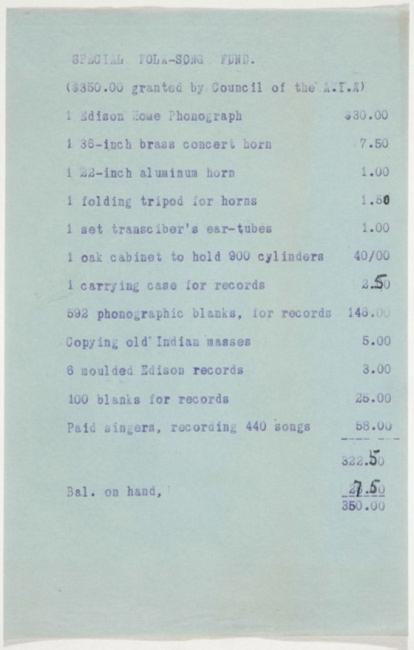

In early 1904, the newly founded Southwest Society undertook its earliest project to record Californio folksongs. Lummis purchased an Edison recorder, horn, and cylinders for $44.25 from H. C. Fiske, Jr. & Co. of Los Angeles. Needing someone to transcribe the songs into musical notations, Lummis engaged the services of Albert Stanley, a professor of music from the University of Michigan. But Lummis wanted someone who would devote himself full-time to transcription and, to his good fortune, he met Arthur Farwell, a noted composer and publisher of music, at a lecture he gave in January 1904.

The AIA provided financial assistance that enabled Farwell to come to California during several summers to work with Lummis. One invoice for Farwell’s first month of work in July–August of 1905 indicated he was paid $50 for his transcriptions. Over the next few years, he transcribed and harmonized several hundred of the songs. (Most of the transcriptions are in the Spanish Song Series in the Lummis Manuscript Collection.)

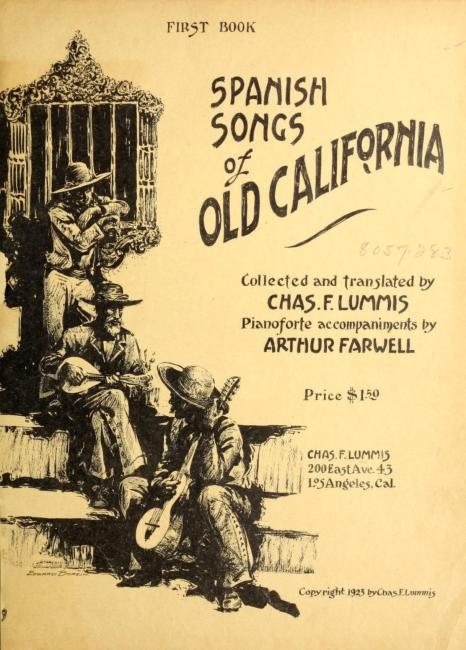

Lummis provided updates and reports of the project’s progress in the Southwest Society meeting minutes, promising that a songbook was forthcoming. But it took almost twenty years to publish just fourteen of the songs.

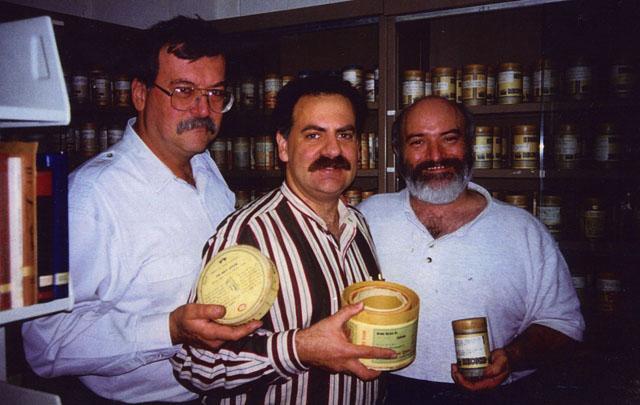

Lummis’s conviction that these cultures were disappearing was largely based on the fact that people in the Southwest who had taught him songs “a decade earlier couldn’t remember them.” Lummis felt that by recording these songs he was preserving “the earliest American Classics” which were on a par with their ancient counterparts from Greece and Rome. Today, we know that the songs haven’t been forgotten. Many people recognize and sing many of the songs. There are groups in Southern California—such as Los Californios of San Diego—that are still performing many of the Lummis recordings.

In a passage from his 1923 Spanish Songs of Old California songbook, Lummis explained:

“Personally, I feel that we who today inherit California are under a filial obligation to save whatever we may of the incomparable Romance which has made the name California a word to conjure with for 400 years. I feel that we can not decently dodge a certain trusteeship to save the Old Missions from ruin and the Old Songs from oblivion. And I am convinced that from a purely selfish standpoint, our musical repertory is in crying need of enrichment—more by heartfelt musicians than by tailor-made ones, more from folksong than from potboilers. For 38 years I have been collecting the old, old songs of the Southwest; beginning long before the phonograph but utilizing that in later years. I have thus recorded more than 450 unpublished Spanish Songs (and know many more in my Attic). It was barely in time; the very people who taught them to me have mostly forgotten them, or died, and few of their children know them. But it is sin and a folly to let each song perish. We need them now.”