During the Progressive Era, women’s clubs flourished among LA’s middle and upper classes. In 1892, over 30 women’s clubs operated in Los Angeles. By the 1920s, that number grew to 172, according to the California Federation of Women’s Clubs (archived at UC Santa Cruz Special Collections). Clubs hosted salons about art, books, travel, science, and music. Club committees worked to solve social ills, preserve local landmarks, create healthier cities, help the war effort, and campaign for suffrage. Collections from of these clubs are can be found at the Autry and peppered throughout Southern California institutions. The Highland Park Ebell Club yearbooks along with the archive from The Assistance League, a woman’s group that started during WW1 as a Red Cross Shop. Occidental College’s Special Collections also has items from the Highland Park Ebell Club. All these club opportunities expanded the idea of how women could create change in their communities and expand and wield their political power.

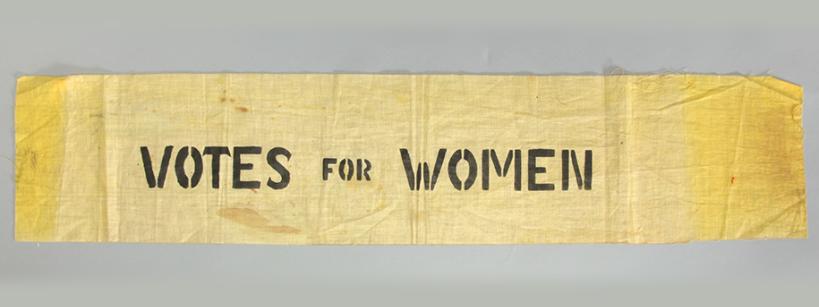

A member of the Friday Morning Club, Mary Foy started her career as the Los Angeles Public Library’s first woman City Librarian and spent the rest of her career working in education and local politics. During California’s 1911 campaign, Foy served as vice president of the Political Equality League and secretary of the Votes for Women Club. A favorite speaker in the suffrage crowd, she did not shy away from creative displays in support of suffrage. The Autry’s Mary Emily Foy collection contains Jane Apostol’s 1996 profile of Foy, titled “Miss Los Angeles.” Apostol recounts a 1911 baseball game in Washington Park at which Foy helped manage a straw vote with an anti-suffrage representative. Both asked baseball fans to vote ‘yes’ or ‘no’ on suffrage. Foy strategically sent a team of women into the crowd to distribute pro-suffrage literature. Ultimately the crowd ‘voted’ in favor of suffrage and even the Los Angeles Times, with its known anti-suffrage bias, acknowledged Foy as the “manager superb and the boss par excellence.” A search on Mary Foy in Calisphere shows that archives and images related to her are found in at least ten different repositories.

Publisher of the California Eagle, Charlotta Bass was another clubwoman who also could have worn the title “Miss Los Angeles” for all her work in advocating for social justice across Los Angeles. According to the Women of the West archives now at the Autry, when Bass arrived in Los Angeles in 1910, she was pleased to join African American women who had been working for the right to vote since the 1890s. According to Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, in her book African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850-1920, the Colored Women’s Club of Los Angeles was one of the early organizations that represented African American women in the west. Bass actively campaigned for voting and civil rights and fought against racial segregation in housing and work. She supported suffrage as well through her editorials in in the African American newspaper The California Eagle she founded with her husband. After her husband’s death, Bass is believed the first African American woman to own and run a newspaper. In 1952, Bass became the first African-American woman nominated for Vice President, as a candidate of the Progressive Party

Attempts to bring out lesser known stories can be seen in large scale projects like the Unladylike2020: Unsung Women Who Changed America one-hour documentary and short films produced and directed by Charlotte Mangin and made available through the Public Broadcast System (PBS). This multimedia series features “courageous, little-known and diverse female trailblazers from the turn of the 20th century.” A feat that brought together hundreds of archival resources not only across Southern California, but from across the country. While small projects like this one-page Women’s Vote Centennial timeline by History Colorado reminds that some groups were still excluded and their struggle to earn the right to vote persisted beyond the passing of the 19th Amendment.

“Researching around” the topic of suffrage resources at the Autry and other archives inspires this historian’s inner-detective—finding, following and pulling at the threads of stories—even more of a challenge considering the reliance on digital archives during a global pandemic. Nonetheless, many institutions like the Autry are “archiving at home” and working to make their collections accessible so that in in 100 years future historians will have more to stitch together about the women in today’s movements.