Exhibitions as Data

By Julia Tcharfas, Collections Cataloger, Autry Museum of the American West

One goal of a museum is to conserve objects in perpetuity—stable and unchanged. By contrast, museum exhibitions are in constant state of flux. Temporary and traveling exhibits are regularly rotating within the gallery walls. Even the so-called permanent galleries undergo numerous transformations over the years.

Exhibitions come and go through a joint museum-wide effort. For museum curators, an exhibition is a carefully chosen group of objects and the labels that tell each object’s story. For the museum design team, the exhibition is a dynamic space constructed as both a conceptual and physical pathway through a theme. Museum marketing might lay claim to the exhibition title, while education staff would script different messaging for different audiences, and so forth. In the end, an exhibition could be thought of as a single whole unit made up of the sum of its parts.

For researchers, studying the history of exhibitions has become just as important as studying the historic artifacts in museum collections. Looking at museum’s exhibition history might reveal the changing trends in programming and design. Perhaps more significantly, it will also reveal the changes in values, tastes, and voices represented in the galleries.

When the Autry Museum of the American West first opened its galleries in 1988, visitors were invited to walk through seven inaugural exhibitions designed by Walt Disney’s Imagineers. These spaces were interrelated through their title, ‘Spirit of:’ Opportunity, Conquest, Community, Cowboy, Discovery, Romance, and Imagination.

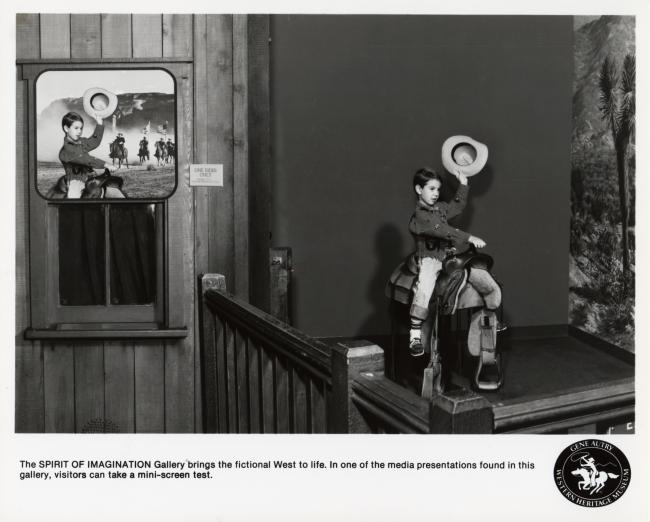

Exhibits were staged over two floors with historic collections on the bottom and art and film artifacts in the galleries above. Visitors moving between the galleries would be faced with the dualities inherent in the founding collection—exploring both the history and the mythology of the ‘American West.’ Downstairs one would walk past displays on the Gold Rush and stories of migration; a historic saloon and cases with artifacts from famous outlaws; original pony express gear and an eclectic array of various work saddles; 19th century tools and clothing of the Vaqueros; and fragments of the lives of Native American cultures. Upstairs, the “imagined West” exhibitions displayed bedazzled costume of the 1950s TV cowboys, film sets and props, children’s toys, dime novels, and film posters. An art gallery showcased iconic Western paintings depicting the real and imagined landscape and people by iconic figures such as Moran, Bierstadt, Remington, John Mix Stanley, Gast, and Melrose.

“Experience the myths. Relive the dramatic history of one of the greatest epics of all times. Return to those ‘exciting days of yesteryear’ when radio, motion pictures, and television featured good guys and bad guys in a struggle to ‘win the West,’” read the Autry Museum of Western Heritage brochure.

Throughout the years these galleries have undergone many changes, and some have been replaced entirely. The museum now has a 32-year long history of rotating thematic exhibitions ranging from Katsina in Hopi Life, Route 66: The Road and the Romance, to the current interactive galleries examining Griffith Park. It has also become a place for significant exhibitions of contemporary Native American artists like Mabel McKay, Rick Bartow, and Harry Fonseca.

How then do we go about cataloging the ever-changing exhibition history?

Images (click for details)

Fig 1. Installation view of the Spirit of Conquest galleries, Autry Museum of the American West, 1990s.

Fig 2. Installation view of the Spirit of Conquest galleries, Autry Museum of the American West, 2000s.

Fig 3. Historic Saloon permanently installed in the Spirit of Community galleries, Autry Museum of the American West, 1990s.

Fig 4. Installation view of the Spirit of the Cowboy galleries, Autry Museum of the American West, 1990s.

Fig 5. Saddles displayed in the Spirit of the Cowboy galleries, Autry Museum of the American West, 1990s.

Fig 6. Mannequins staged with the chuckwagon in the Spirit of the Cowboy galleries, Autry Museum of the American West, 1990s.

Fig 7. A detail view of the mannequins staged as part of the O.K. Corral installation, Autry Museum of the American West, 1990s.

Fig 8. A child posing in an interactive green screen display in the Spirit of Imagination galleries, Autry Museum of the American West,1990s.

This January, I embarked on a long-term project to create a new section in our collections database with data driven linked exhibition history. I’ve compiled a list of nearly 400 exhibitions from both the Autry Museum and the Historic Southwest Museum of the American Indian beginning in 1983 to the present. (My goal is to eventually trace the Southwest Museum history as far back as its opening in 1914.) In our database, each exhibition record contains descriptive text and dates. These records are then linked to the objects, loans, people, publications, as well as the installation images associated with each exhibition. In that sense each exhibition record is dynamic and can lead to-and-from the different sections of the database. The exhibition data can be searched and stumbled upon in myriad of ways.

In order to compile the exhibitions data, I am working with our Institutional Archive, Loans and Exhibitions Registrar, Librarian, and Photographer. Each has supplied me with lists I can turn into links in the database. I have also combed through old exhibition catalogs and newspaper archives for object lists and descriptions. The exhibitions database will be yet another way for accessing and searching our collections on display. This work is ongoing and will certainly serve as an important repository at their fingertips of our staff and museum researchers interested in our exhibition history.

Image Captions

- Fig 1. Installation view of the Spirit of Conquest galleries, Autry Museum of the American West, 1990s.

- Fig 2. Installation view of the Spirit of Conquest galleries, Autry Museum of the American West, 2000s.

- Fig 3. Historic Saloon permanently installed in the Spirit of Community galleries, Autry Museum of the American West, 1990s.

- Fig 4. Installation view of the Spirit of the Cowboy galleries, Autry Museum of the American West, 1990s.

- Fig 5. Saddles displayed in the Spirit of the Cowboy galleries, Autry Museum of the American West, 1990s.

- Fig 6. Mannequins staged with the chuckwagon in the Spirit of the Cowboy galleries, Autry Museum of the American West, 1990s.

- Fig 7. A detail view of the mannequins staged as part of the O.K. Corral installation, Autry Museum of the American West, 1990s.

- Fig 8. A child posing in an interactive green screen display in the Spirit of Imagination galleries, Autry Museum of the American West,1990s.